We are often asked if permaculture means using only native plants, or on the flip side, if permaculture advocates for using “invasive” species. I put “invasive” in quotes because there is a lot to unpack in that sentiment alone. It’s a complex question and one I would love to explore a little bit together.

THE CARE FOR NATIVE SPECIES

There’s no doctrine in permaculture that specifies using native plants, but one of the key directives of permaculture design is valuing and restoring biodiversity. Naturally, native plants are a massive asset in restoring biodiversity and building ecological resilience for myriad reasons.

Beebalm

- Native plants are specifically adapted to a bioregional climate, and when well-sited, can thrive with minimal inputs, thus reducing the need for irrigation or fertilizers.

- They are mostly disease resistant and flourish without the use of herbicides or pesticides.

- Native species have co-evolved with certain insects, bacteria, and fungi, and therefore, play a key role in the larger food web and soil biome. Introducing native plants into your landscape helps native biodiversity flourish.

- Native species are often choked out of their habitats by more aggressive and unmanaged species, especially in urban/suburban areas, so planting them is an act of conserving biodiversity.

The case for non-native species

This is a huge topic and one clouded by lots of dogma on both sides of the aisle. Here are a few key arguments in favor of planting non-native species.

Asian Persimmon

- The world is a dynamic and changing environment, accelerated by globalization. Planting certain species that do not have an analogous native alternative can facilitate resilience.

- The climate is changing, and many native species that occupy particular ecological niches are being threatened, for example, the Eastern Hemlock. Many ecologists advocate for planting non-native alternatives that fit the specific niche to not cause ecological collapse should the native species go extinct.

- Plants typically classified as “invasive” are often doing the tireless and thankless work of rapid earth repair, particularly in degraded post-development urban and suburban landscapes. They are attracting nutrients through prolific fruiting and supporting wildlife; they build topsoil; they are reintroducing nitrogen. There’s a case to be made for letting nature take its course and trusting the innate intelligence of natural systems to self-regulate (even beyond our human timeframe).

- We live in a post-wild world. Building resilient food systems means augmenting annual agriculture with wild and cultivated perennial food sources, such as nuts, fruits, berries, and edible greens.

You could go down a rabbit hole of research and find evidence for both arguments. Check out our curated resource list for lots of great books on the topic. Depending on who you talk to, you will get lots of different answers to these questions.

Here’s our take

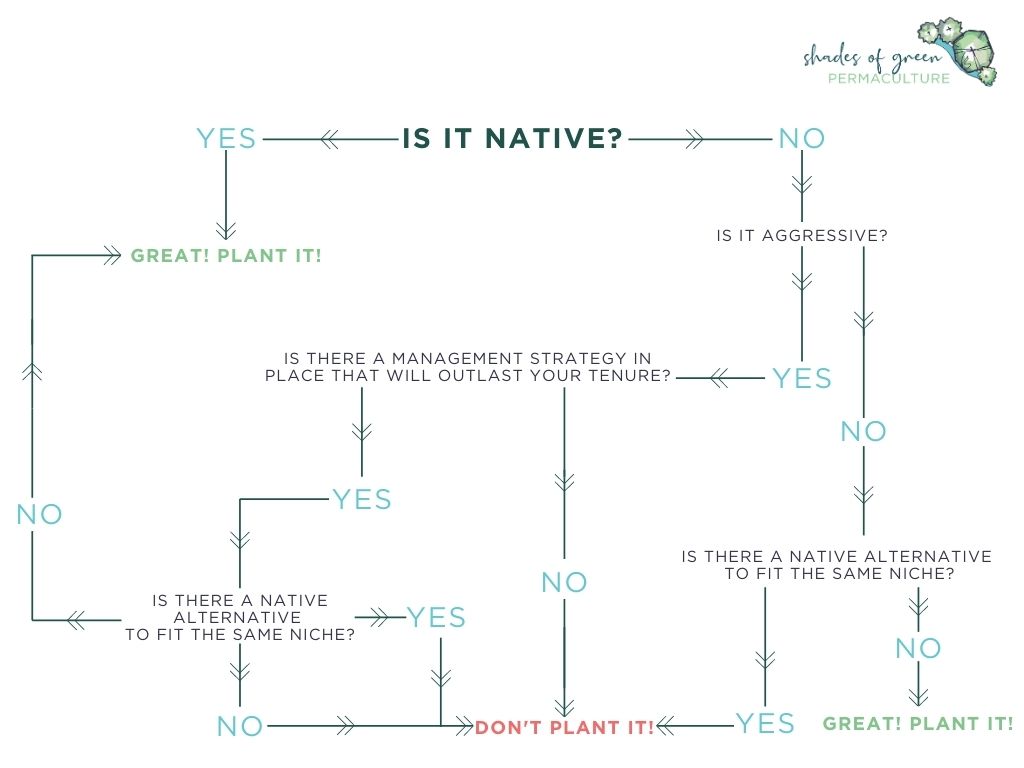

Here is the decision-making framework we use when we are considering introducing a plant into a landscape, assuming it also meets other criteria and serves multiple functions:

There are many nuances in determining the merits of introducing individual plants into a landscape, such as what it yields, how many functions it has within the landscape, whether or not it offers ecosystem services, which niche it fills, etc. I’ll save that for another blog post, so stay tuned!