One of the many tools in our tool belt in permaculture design is to consider “zones of use.” While Zones of Use can be a helpful lens with which to plan a maximally productive garden, it’s often touted as permaculture gospel. Instead, I want to discuss the relevance of “zones of use” in a home-scale edible landscape, where the primary goal is not necessarily productivity.

I sat down to write a post about Zones of Use, but I want to preface this whole post by telling you that I spend a lot of time thinking about the current state of the world and the ways we can come back into “right relationship” with nature, the wild, and one another. I think about reverence, and even while I’m entrenched in a capitalist system, and I spend my work hours optimizing and systematizing, I dream of a time beyond my own when beauty and life and peace are our highest collective aspirations.

So, now that you know what you’re in for do you want to go on a ramble with me?

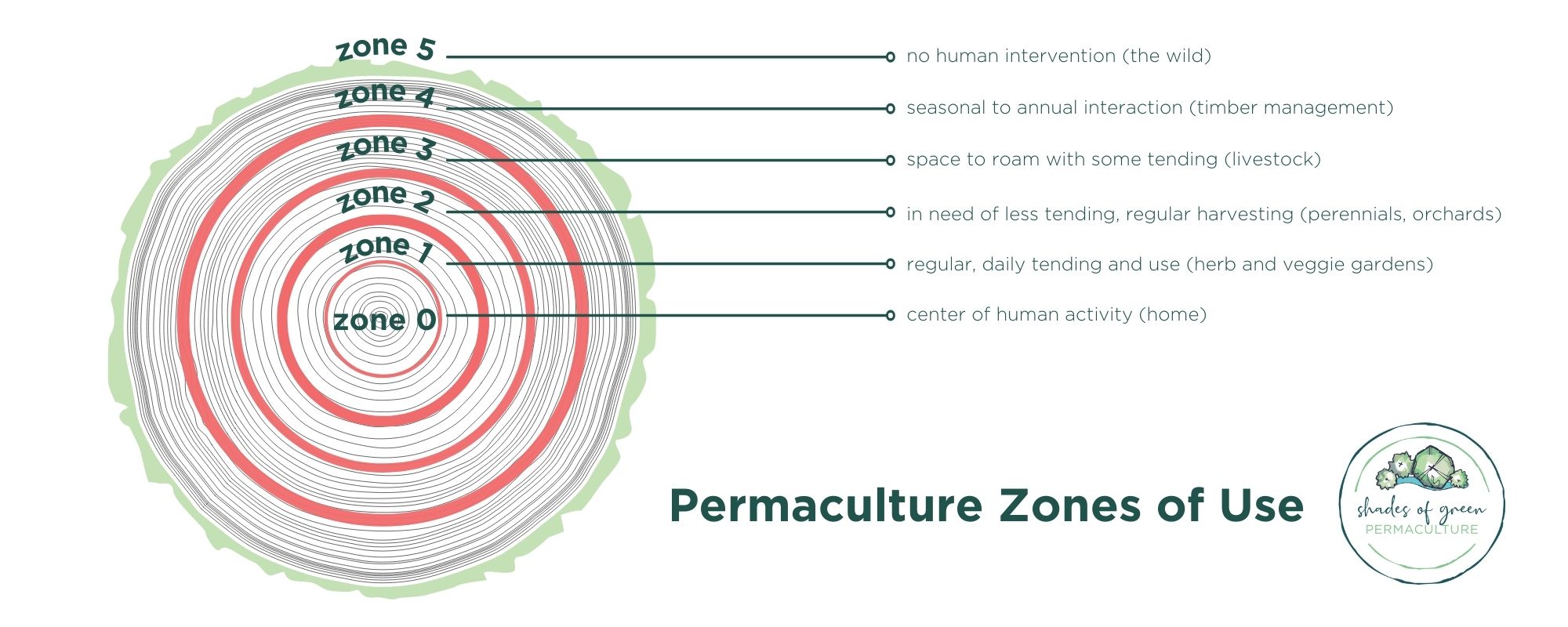

Before we dissect the Zones of Use, let’s first define them. The Zones of Use are loosely defined as:

Since many urban or suburban landscapes are neither large enough to truly implement distinct “zones” nor specifically oriented toward maximum harvest, they tend to be patterned in a way that works with the ideal conditions for different elements such as veggie gardens and fruit trees. And few, if any, represent all five zones. Additionally, it is, in my opinion, just as important to restore water cycles, bolster biodiversity, build soil, capture carbon, and create habitat in disturbed urban residential landscapes as it is to produce food. I think it’s relevant to remember that the overall goal of utilizing “zones” to organize space is to optimize the way a site is laid out for maximum efficiency.

But, as we live in a world that values efficiency over all else, I ask, is efficiency truly the goal?

For me, it feels a bit extractive. I’m not in my garden to be efficient. I’m in my garden to learn, to observe, and to relate. I want to see how the dappled light changes each day. I want to lay in the soft grass and watch the mimosa blossoms sway in the breeze. I want to hear the chit-chat of warblers pecking through the leaf litter on the forest floor, looking for dinner. I want to see my daughter chomp on fennel and sorrel, teaching me the names of her plants. Gardening, for me, is about healing, where I try with my hands and my songs to court the Holy in Nature rather than coerce her.

So, no, for me, efficiency is not necessarily the goal.

We often get inquiries about no-maintenance landscapes. I’d say, if you’re looking to cultivate a garden specifically for food, herbs, flowers, habitat, open space, outdoor entertaining, or myriad other human uses, “no maintenance” doesn’t exist—the dirty “M” word. But, you could think of maintenance as a relationship⏤a little bit of give and take. One of my mentors, Chuck Marsh, used to say “maintenance is love,” and I wholeheartedly agree. It’s akin to the feeling I get when I clear the cobwebs from the corners of my house: it leaves me feeling so happy to have tended to my space as if life somehow makes a little more sense. Restoring my home to a place of “tended” restores me.

Of course, as a city dweller with a full-time job that keeps me from my garden day in and day out, I understand the time constraints. That’s one of the beauties of ecological landscapes⏤you do the work to set up a responsive and regenerative garden. Once the stage is set, the natural intelligence of a place can express itself while yielding many benefits. Maintenance becomes tending, noticing, exerting occasionally, and ultimately surrendering to the innate beauty and intelligence of the land.

Are you still with me? So, to bring it back to Zones of Use…

If you’re in an urban or suburban landscape, and your goal is not a maximally efficient and productive landscape (as in, you aren’t farming), dare I say, DITCH THE ZONES. Instead, learn from the wild and be wildly inefficient in your learning. Take your time. Organize your landscape to meet your goals, utilize the natural assets, and recalibrate your goals to be realistic about what you’re willing to invest in the relationship. Value reciprocity: be willing to feed in order to be fed, not the other way around. These are my aspirations. #gardengoals

I was looking for a quote to punctuate this idea today and came across this passage from a long-time teacher of mine, Martín Prechtel. I’ll leave you with this food for thought:

“Everything in Nature ran according to its own nature; the running of grass was in its growing, the running of rivers their flowing, granite bubbled up, cooled, compressed and crumbled, birds lived, flew, sang and died, everything did what it needed to do, each simultaneously running its own race, each by living according to its own nature together, never leaving any other part of the universe behind. The world’s Holy things constantly raced together, not to win anything over the next, but to keep the entire surging diverse motion of the living world from grinding to a halt, which is why there is no end to that race; no finish line. That would be oblivion to all.

For the Indigenous Souls of all people who can still remember how to be real cultures, life is a race to be elegantly run, not a race to be competitively won. It cannot be won; it is the gift of the world’s diverse, beautiful motion that must be maintained because human life has been given the gift of our elegant motion. Whether we limp, roll, crawl, stroll, or fly, it is an obligation to engender that elegance of motion in our daily lives in service of maintaining life by moving and living as beautifully as we can. All else has, to me, the familiar taste of that domineering warlike harshness that daily tries to cover its tracks to camouflage the deep ruts of some old, sick, grinding, ungainly need to flee away from the elegance of our original Indigenous human souls. Our attempt to avariciously conquer or win a place where there are no problems, whether it be Heaven or a “New Democracy,” never mind if it is spiritually ugly and immorally “won” and taken from someone who is already there, has made a citifying world of people who, unconscious of it, have become our own ogreish problem to ourselves, our future, and the world. This is a problem that we cannot continue to attempt to competitively outrun by more and more effectively designed technological approaches to speed away from the past, for the specter of our own earth-wasting reality runs grinning competitively right alongside us. By developing even more effective and entertaining methods of escape that only burn up the earth, the air, animals, plants, and the deeper substance of what it should mean to be human, by competing to get ahead, we have created a brakeless competition that has outrun our innate beauty and marked out a very definite and imminent “finish” line.

Living in and on a sphere, we cannot really outrun ourselves anyway. Therefore, I say, the entire devastating and hideous state of the world and its constant wounding and wrecking of the wild, beautiful, natural, viable and small, only to keep alive an untenable cultural proceedance is truly a spiritual sickness, one that will not be cured by the efficient use of the same thinking that maintains the sickness. Nor can this overly expensive, highly funded illness be symptomatically kept at bay any longer by yet more political, environmental, or social programs.

We must, as individuals and communities, take the time necessary to learn how to indigenously remember what a sane, original existence for a viable people might look like.

Though there are marvelous things and amazing people doing them, both seen and unseen, these do not resemble in any way the general trend of what is going on now.

To begin remembering our Indigenous belonging on the Earth back to life, we must metabolize as individuals the grief of recognition of our lost directions, digest it into a valuable spiritual compost that allows us to learn to stay put without outrunning our strange past and get small, unarmed, brave, and beautiful.

By trying to feed the Holy in Nature the fruit of beauty from the tree of memory of our Indigenous Souls, grown in the composted failures of our past need to conquer, watered by the tears of cultural grief, we might become ancestors worth descending from and possibly grow a place of hope for a time beyond our own.”

―Martin Prechtel, The Unlikely Peace at Cuchumaquic: The Parallel Lives of People as Plants: Keeping the Seeds Alive